Cryptography

https://ctf101.org/cryptography/overview/

Cryptography is the reason we can use banking apps, transmit sensitive information over the web, and in general protect our privacy. However, a large part of CTFs is breaking widely used encryption schemes that are improperly implemented. The math may seem daunting, but more often than not, a simple understanding of the underlying principles will allow you to find flaws and crack the code.

The word “cryptography” technically means the art of writing codes. When it comes to digital forensics, it’s a method you can use to understand how data is constructed for your analysis.

What is cryptography used for?

Uses in everyday software

- Securing web traffic (passwords, communication, etc.)

- Securing copyrighted software code

Malicious uses

- Hiding malicious communication

- Hiding malicious code

Topics

- XOR

- Cesear Cipher

- Substitution Cipher

- Vigenere Cipher

- Hashing Functions

- Block Ciphers

- Stream Ciphers

- RSA

XOR

Data Representation

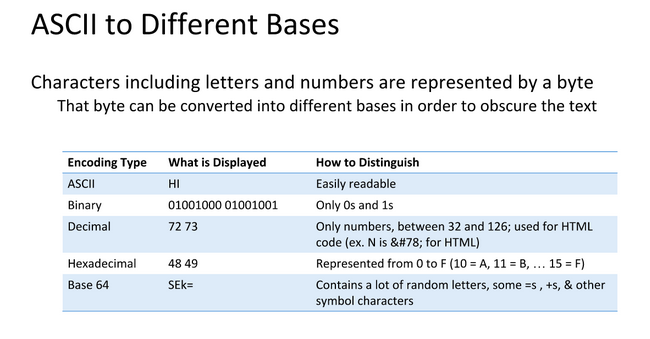

Data can be represented in different bases, an 'A' needs to be a numerical representation of Base 2 or binary so computers can understand them

XOR Basics

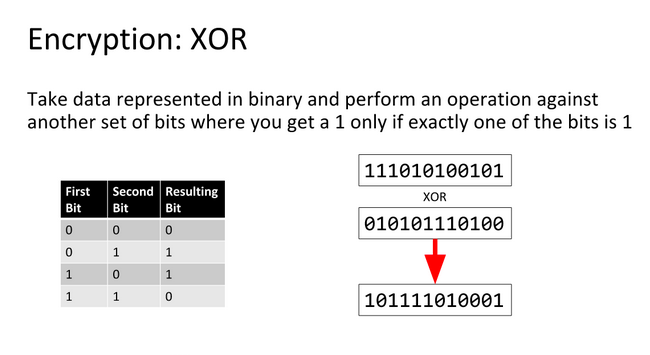

An XOR or eXclusive OR is a bitwise operation indicated by ^ and shown by the following truth table:

| A | B | A ^ B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

So what XOR'ing bytes in the action 0xA0 ^ 0x2C translates to is:

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|---|

0b10001100` is equivalent to `0x8C`, a cool property of XOR is that it is reversible meaning `0x8C ^ 0x2C = 0xA0` and `0x8C ^ 0xA0 = 0x2C

What does this have to do with CTF?

XOR is a cheap way to encrypt data with a password. Any data can be encrypted using XOR as shown in this Python example:

>>> data = 'CAPTURETHEFLAG'

>>> key = 'A'

>>> encrypted = ''.join([chr(ord(x) ^ ord(key)) for x in data])

>>> encrypted

'\x02\x00\x11\x15\x14\x13\x04\x15\t\x04\x07\r\x00\x06'

>>> decrypted = ''.join([chr(ord(x) ^ ord(key)) for x in encrypted])

>>> decrypted

'CAPTURETHEFLAG'

This can be extended using a multibyte key by iterating in parallel with the data.

Exploiting XOR Encryption

Single Byte XOR Encryption

Single Byte XOR Encryption is trivial to bruteforce as there are only 255 key combinations to try.

Multibyte XOR Encryption

Multibyte XOR gets exponentially harder the longer the key, but if the encrypted text is long enough, character frequency analysis is a viable method to find the key. Character Frequency Analysis means that we split the cipher text into groups based on the number of characters in the key. These groups then are bruteforced using the idea that some letters appear more frequently in the English alphabet than others.

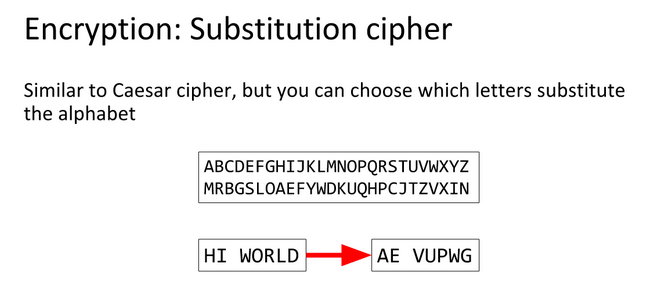

Substitution Cipher

A Substitution Cipher is a system of encryption where different symbols substitute a normal alphabet.

Caesar Cipher/ROT 13

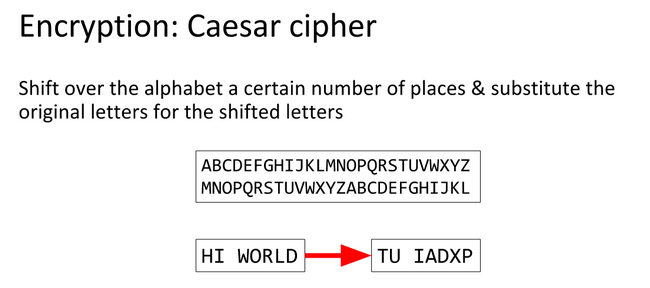

The Caesar Cipher or Caesar Shift is a cipher that uses the alphabet to encode texts.

CAESAR` encoded with a shift of 8 is `KIMAIZ` so `ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ` becomes `IJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGH

ROT13 is the same thing but a fixed shift of 13, this is a trivial cipher to bruteforce because there are only 25 shifts.

Vigenere Cipher

A Vigenere Cipher is an extended Caesar Cipher where a message is encrypted using various Caesar-shifted alphabets.

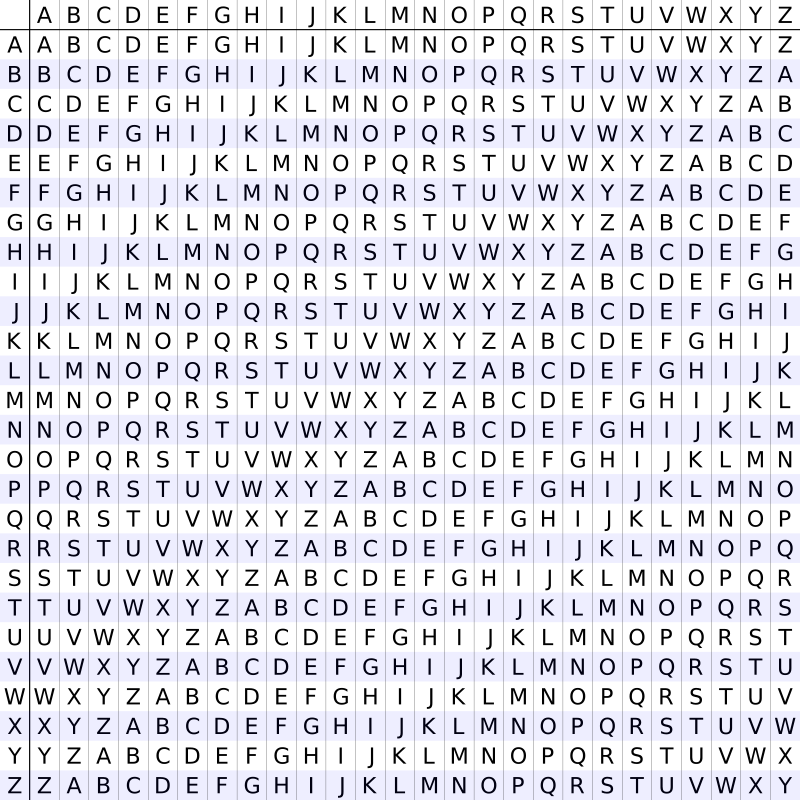

The following table can be used to encode a message:

Encryption

For example, encrypting the text SUPERSECRET with CODE would follow this process:

CODEgets padded to the length ofSUPERSECRETso the key becomesCODECODECOD- For each letter in

SUPERSECRETwe use the table to get the Alphabet to use, in this instance rowCand columnS - The ciphertext's first letter then becomes

U - We eventually get

UISITGHGTSW

Decryption

- Go to the row of the key, in this case,

C - Find the letter of the cipher text in this row, in this case

U - The column is the first letter of the decrypted ciphertext, so we get

S - After repeating this process we get back to

SUPERSECRET

Hashing Functions

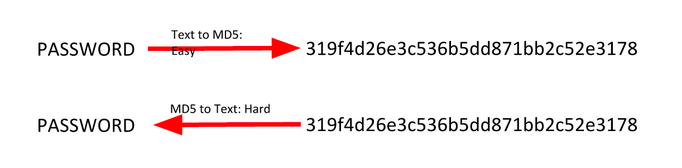

Hashing functions are one-way functions that theoretically provide a unique output for every input. MD5, SHA-1, and other hashes which were considered secure are now found to have collisions or two different pieces of data which produce the same supposed unique output.

String Hashing

A string hash is a number or string generated using an algorithm that runs on text or data.

The idea is that each hash should be unique to the text or data (although sometimes it isn’t). For example, the hash for “dog” should be different from other hashes.

You can use command line tools or online resources such as this one. Example: $ echo -n password | md5 5f4dcc3b5aa765d61d8327deb882cf99 Here, “password” is hashed with different hashing algorithms:

- SHA-1: 5BAA61E4C9B93F3F0682250B6CF8331B7EE68FD8

- SHA-2: 5E884898DA28047151D0E56F8DC6292773603D0D6AABBDD62A11EF721D1542D8

- MD5: 5F4DCC3B5AA765D61D8327DEB882CF99

- CRC32: BBEDA74F

Generally, when verifying a hash visually, you can simply look at the first and last four characters of the string.

File Hashing

A file hash is a number or string generated using an algorithm that is run on text or data. The premise is that it should be unique to the text or data. If the file or text changes in any way, the hash will change.

What is it used for? - File and data identification - Password/certificate storage comparison

How can we determine the hash of a file? You can use the md5sum command (or similar).

$ md5sum samplefile.txt

3b85ec9ab2984b91070128be6aae25eb samplefile.txt

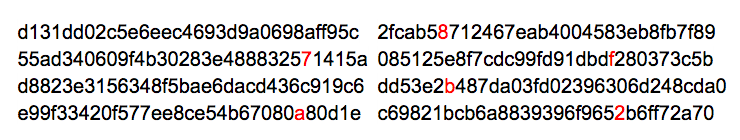

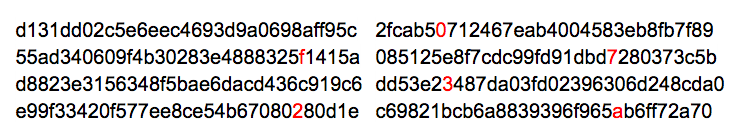

Hash Collisions

A collision is when two pieces of data or text have the same cryptographic hash. This is very rare.

What’s significant about collisions is that they can be used to crack password hashes. Passwords are usually stored as hashes on a computer since it’s hard to get the passwords from hashes.

If you bruteforce by trying every possible piece of text or data, eventually you’ll find something with the same hash. Enter it, and the computer accepts it as if you entered the actual password.

Two different files on the same hard drive with the same cryptographic hash can be very interesting.

“It’s now well-known that the cryptographic hash function MD5 has been broken,” said Peter Selinger of Dalhousie University. “In March 2005, Xiaoyun Wang and Hongbo Yu of Shandong University in China published an article in which they described an algorithm that can find two different sequences of 128 bytes with the same MD5 hash.”

For example, he cited this famous pair:

and

Each of these blocks has MD5 hash 79054025255fb1a26e4bc422aef54eb4.

Selinger said that “the algorithm of Wang and Yu can be used to create files of arbitrary length that have identical MD5 hashes, and that differ only in 128 bytes somewhere in the middle of the file. Several people have used this technique to create pairs of interesting files with identical MD5 hashes.”

Ben Laurie has a nice website that visualizes this MD5 collision. For a non-technical, though slightly outdated, introduction to hash functions, see Steve Friedl’s Illustrated Guide. And here’s a good article from DFI News that explores the same topic.

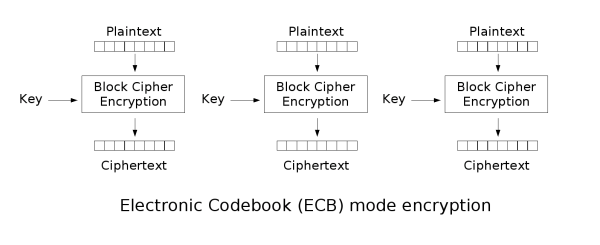

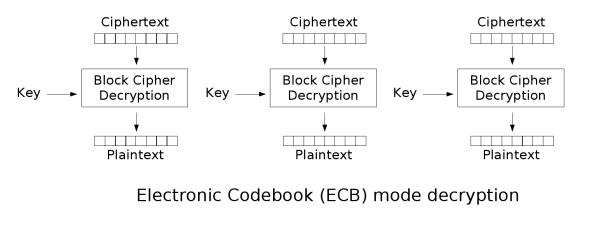

Block Ciphers

A Block Cipher is an algorithm that is used in conjunction with a cryptosystem to package a message into evenly distributed 'blocks' which are encrypted one at a time.

Definitions

- Mode of Operation: How a block cipher is applied to an amount of data that exceeds a block's size

- Initialization Vector (IV): A sequence of bytes that is used to randomize encryption even if the same plaintext is encrypted

- Starting Variable (SV): Similar to the IV, except it is used during the first block to provide a random seed during encryption

- Padding: Padding is used to ensure that the block sizes all line up and ensure the last block fits the block cipher

- Plaintext: Unencrypted text; Data without obfuscation

- Key: A secret used to encrypt plaintext

- Ciphertext: Plaintext encrypted with a key

Common Block Ciphers

| Mode | Formulas | Ciphertext |

|---|---|---|

| ECB | Yi = F(PlainTexti, Key) | Yi |

| CBC | Yi = PlainTexti XOR Ciphertexti-1 | F(Y, key); Ciphertext0 = IV |

| PCBC | Yi = PlainTexti XOR (Ciphertexti-1 XOR PlainTexti-1) | F(Y, key); Ciphertext0 = IV |

| CFB | Yi = Ciphertexti-1 | Plaintext XOR F(Y, key); Ciphertext0 = IV |

| OFB | Yi = F(Key, Ii-1);Y0=IV | Plaintext XOR Yi |

| CTR | Yi = F(Key, IV + g(i));IV = token(); | Plaintext XOR Yi |

Note

In this case, i represents an index over the # of blocks in the plaintext. F() and g() represent the function used to convert plaintext into ciphertext.

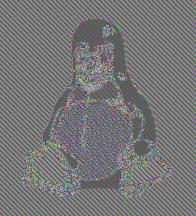

Electronic Codebook (ECB)

ECB is the most basic block cipher, it simply chunks up plaintext into blocks and independently encrypts those blocks, and chains them all into a ciphertext.

Flaws

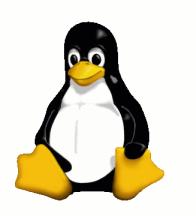

Because ECB independently encrypts the blocks, patterns in data can still be seen clearly, as shown in the CBC Penguin image below.

| Original Image | ECB Image | Other Block Cipher Modes |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

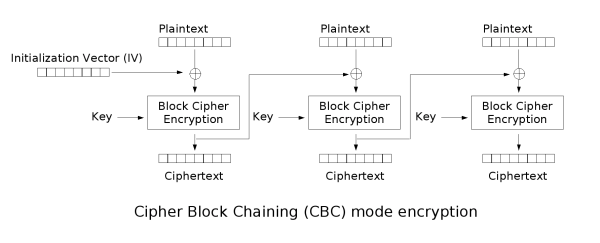

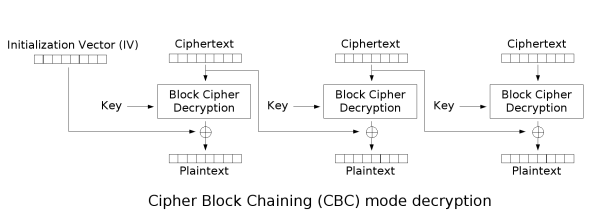

Cipher Block Chaining (CBC)

CBC is an improvement upon ECB where an Initialization Vector is used to add randomness. The encrypted previous block is used as the IV for each sequential block meaning that the encryption process cannot be parallelized. CBC has been declining in popularity due to a variety of

Note

Even though the encryption process cannot be parallelized, the decryption process can be parallelized. If the wrong IV is used for decryption it will only affect the first block as the decryption of all other blocks depends on the ciphertext not the plaintext.

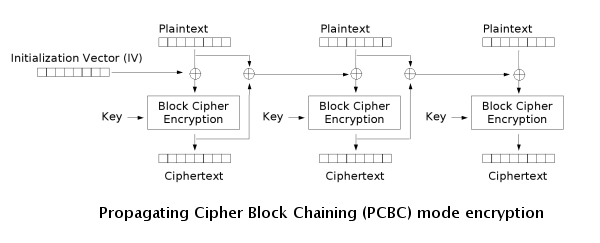

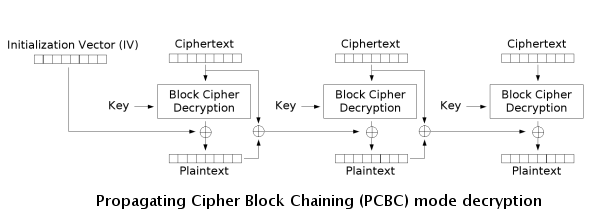

Propagating Cipher Block Chaining (PCBC)

PCBC is a less-used cipher that modifies CBC so that decryption is also not parallelizable. It also cannot be decrypted from any point as changes made during the decryption and encryption process "propagate" throughout the blocks, meaning that both the plaintext and ciphertext are used when encrypting or decrypting as seen in the images below.

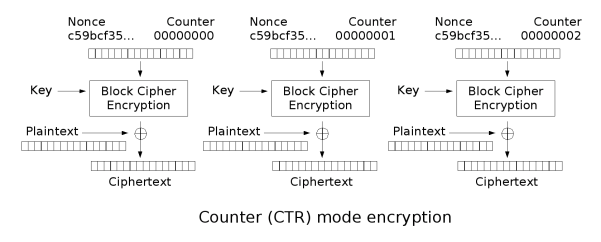

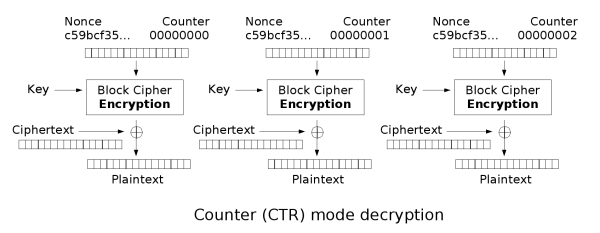

Counter (CTR)

Note

The counter is also known as CM, integer counter mode (ICM), and segmented integer counter (SIC)

CTR mode makes the block cipher similar to a stream cipher and it functions by adding a counter with each block in combination with a nonce and key to XOR the plaintext to produce the ciphertext. Similarly, the decryption process is the same except instead of XORing the plaintext, the ciphertext is XORed. This means that the process is parallelizable for both encryption and decryption and you can begin from anywhere as the counter for any block can be deduced easily.

Security Considerations

If the nonce chosen is non-random, it is important to concatenate the nonce with the counter (high 64 bits to the nonce, low 64 bits to the counter) as adding or XORing the nonce with the counter would break security as an attacker can cause a collision with the nonce and counter. An attacker with access to providing a plaintext, nonce, and counter can then decrypt a block by using the ciphertext as seen in the decryption image.

Padding Oracle Attack

A Padding Oracle Attack sounds complex but essentially means abusing a block cipher by changing the length of input and being able to determine the plaintext.

Requirements

- An oracle, or program, which encrypts data using CBC

- Continual use of the same key

Execution

- If we have two blocks of ciphertext, C1, and C2, we can get the plaintext P2

- Since we know that CBC decryption is dependent on the prior ciphertext if we change the last byte of C1 we can see if C2 has the correct padding

- If it is correctly padded we know that the last byte of the plaintext

- If not, we can increase our byte by one and repeat until we have a successful padding

- We then repeat this for all successive bytes following C1 and if the block is 16 bytes we can expect a maximum of 4080 attempts which is trivial

Stream Ciphers

A Stream Cipher is used for symmetric key cryptography, or when the same key is used to encrypt and decrypt data. Stream Ciphers encrypt pseudorandom sequences with bits of plaintext to generate ciphertext, usually with XOR. A good way to think about Stream Ciphers is to think of them as generating one-time pads from a given state.

Definitions

- A keystream is a sequence of pseudorandom digits that extend to the length of the plaintext to uniquely encrypt each character based on the corresponding digit in the keystream

One-Time Pads

A one-time pad is an encryption mechanism whereby the entire plaintext is XOR'd with a random sequence of numbers to generate a random ciphertext. The advantage of the one-time pad is that it offers an immense amount of security BUT for it to be useful, the randomly generated key must be distributed on a separate secure channel, meaning that one-time pads have little use in modern-day cryptographic applications on the internet. Stream ciphers extend upon this idea by using a key, usually 128-bit in length, to seed a pseudorandom keystream which is used to encrypt the text.

Types of Stream Ciphers

Synchronous Stream Ciphers

A Synchronous Stream Cipher generates a keystream based on internal states not related to the plaintext or ciphertext. This means that the stream is generated pseudorandomly outside of the context of what is being encrypted. A binary additive stream cipher is the term used for a stream cipher in which XOR's the bits with the bits of the plaintext. Encryption and decryption require that the synchronous state cipher is in the same state, otherwise, the message cannot be decrypted.

Self-synchronizing Stream Ciphers

A Self-synchronizing Stream Cipher, also known as an asynchronous stream cipher or ciphertext autokey (CTAK), is a stream cipher that uses the previous N digits to compute the keystream used for the next N characters.

Note

Seems a lot like block ciphers doesn't it? That's because block cipher feedback mode (CFB) is an example of a self-synchronizing stream cipher.

Stream Cipher Vulnerabilities

Key Reuse

The key tenet of using stream ciphers securely is to NEVER repeat key use because of the commutative property of XOR. If C1 and C2 have been XOR'd with a key K, retrieving that key K is trivial because C1 XOR C2 = P1 XOR P2, and having an English language-based XOR means that cryptoanalysis tools such as a character frequency analysis will work well due to the low entropy of the English language.

Bit-flipping Attack

Another key tenet of using stream ciphers securely is considering that just because a message has been decrypted, it does not mean the message has not been tampered with. Because decryption is based on state, if an attacker knows the layout of the plaintext, a Man in the Middle (MITM) attack can flip a bit during transit altering the underlying ciphertext. If a ciphertext decrypts to 'Transfer $1000', then a middleman can flip a single bit for the ciphertext to decrypt to 'Transfer $9000' because changing a single character in the ciphertext does not affect the state in a synchronous stream cipher.

RSA

RSA, which is an abbreviation of the author's name (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman), is a cryptosystem that allows for asymmetric encryption. Asymmetric cryptosystems are also commonly referred to as Public Key Cryptography where a public key is used to encrypt data and only a secret, a private key can be used to decrypt the data.

Definitions

- The Public Key is made up of (n, e)

- The Private Key is made up of (n, d)

- The message is represented as m and is converted into a number

- The encrypted message or ciphertext is represented by c

- p and q are prime numbers which make up n

- e is the public exponent

- n is the modulus and its length in bits is the bit length (i.e. 1024 bit RSA)

- d is the private exponent

- The totient λ(n) is used to compute d and is equal to the lcm(p-1, q-1), another definition for λ(n) is that λ(pq) = lcm(λ(p), λ(q))

What makes RSA viable?

If public n, public e, private d are all very large numbers and a message m holds true for 0 < m < n, then we can say:

(m^e)d ≡ m (mod n)

Note

The triple equals sign in this case refers to modular congruence which in this case means that there exists an integer k such that (m^e)d = kn + m

RSA is viable because it is incredibly hard to find d even with m, n, and e because factoring large numbers is an arduous process.

Implementation

RSA follows 4 steps to be implemented: 1. Key Generation 2. Encryption 3. Decryption

Key Generation

We are going to follow Wikipedia's small numbers example to make this idea a bit easier to understand.

Note

In This example, we are using Carmichael's totient function where λ(n) = lcm(λ(p), λ(q)), but Euler's totient function is perfectly valid to use with RSA. Euler's totient is φ(n) = (p − 1)(q − 1)

- Choose two prime numbers such as:

- p = 61 and q = 53

- Find n:

- n = pq = 3233

- Calculate λ(n) = lcm(p-1, q-1)

- λ(3233) = lcm(60, 52) = 780

- Choose a public exponent such that 1 < e < λ(n) and is coprime (not a factor of) λ(n). The standard in most cases is 65537, but we will be using:

- e = 17

- Calculate d as the modular multiplicative inverse or in English find d such that:

de mod λ(n) = 1- d * 17 mod 780 = 1

- d = 413

Now we have a public key of (3233, 17) and a private key of (3233, 413)

Encryption

With the public key, m can be encrypted trivially

The ciphertext is equal to m**e mod n or:

c = m^17 mod 3233

Decryption

With the private key, m can be decrypted trivially as well

The plaintext is equal to c**d mod n or:

m = c^413 mod 3233

Exploitation

From the RsaCtfTool README

Attacks:

- Weak public key factorization

- Wiener's attack

- Hastad's attack (Small public exponent attack)

- Small q (q < 100,000)

- Common factor between ciphertext and modulus attack

- Fermat's factorization for close p and q

- Gimmicky Primes method

- Past CTF Primes method

- Self-Initializing Quadratic Sieve (SIQS) using Yafu

- Common factor attacks across multiple keys

- Small fractions method when p/q is close to a small fraction

- Boneh Durfee Method when the private exponent d is too small compared to the modulus (i.e d < n^0.292)

- Elliptic Curve Method

- Pollards p-1 for relatively smooth numbers

- Mersenne primes factorization